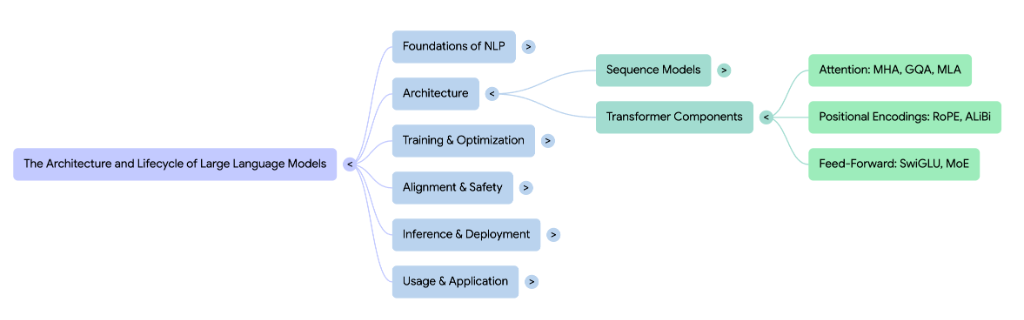

We are about to touch the holy grail of modern AI. The 2017 declaration was simple: Attention Is All You Need. But as we’ve raced from GPT-1 to reasoning models, the definition of ‘Attention’ has quietly transformed. Is the algorithm ruling the world today actually the same one we started with? Let’s look under the hood.

🔥 The Core Concept

At its heart, the attention mechanism is a form of weighted aggregation. It is often described using a database retrieval analogy. Imagine you have a database of information (context).

- Query ($Q$): What are you currently looking for? (The token being generated).

- Key ($K$): The indexing tag associated with each piece of information.

- Value ($V$): The actual information (The context token).

The “Attention” is the process of matching your Query against all the Keys to determine how much “weight” to put on each Value. Attention scores are calculated in each transformer layer at every step of the sequence. This is a single unifying factor in all transformer models, from BERT to Gemini.

🔥 Standard Multi-Head Attention (MHA)

The original mechanism introduced in the paper “Attention Is All You Need”.

Here, instead of performing the Key-Query-Value (KQV) operation on the entire context only once, the attention is split into $N$ parallel heads. Each head learns a different aspect of the language (e.g., word meaning, syntax, semantic relationships, etc.). The equation is a simple culmination of dot products aided by a regularizer like Softmax.

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V $$

Where:

- $QK^T$ computes the similarity scores between the Query and Key.

- $\sqrt{d_k}$ is a scaling factor to prevent the dot product from growing too large, mitigating the vanishing/exploding gradient problem.

- The weighted sum is applied to the values of $V$.

The Memory Bandwidth Bottleneck: > During inference, the model must store Key and Value matrices for all previous tokens. This is called the KV Cache. In MHA, every single head has its own unique set of Keys and Values. For large models with massive context windows, loading this massive KV cache from memory (HBM) to the computation chip (SRAM) becomes the primary bottleneck, slowing down generation significantly. Earlier models could often only generate ~8 tokens per second at inference due to this constraint.

🔥 Multi-Query Attention (MQA)

This approach addresses the memory bottleneck by sharing the same set of Keys and Values across all heads while keeping separate Query heads.

- MHA: $H$ Query heads, $H$ Key heads, $H$ Value heads

- MQA: $H$ Query heads, 1 Key head, 1 Value head

This drastically reduces the memory requirements of the KV cache by a factor of $H$ (often 8x or 16x). The GPU needs to load far less data, significantly speeding up inference. However, it does not reduce the computation (FLOPs)—so why is it faster?

This can be explained with the Kitchen Analogy: Imagine a kitchen (GPU) with 8 chefs (Heads).

- Computation (Math): The Chef chopping vegetables.

- Memory Access (Bandwidth): The Assistant running to the fridge to get ingredients.

In MHA: Each chef demands unique vegetables from the fridge. The assistant runs back and forth 8 times, fetching 8 different crates. Most of the time is spent waiting for the assistant to return. This results in idle cores waiting for data to load from HBM.

In MQA: All chefs agree to use the same vegetables. The assistant runs back and forth only once, fetching one giant crate of potatoes and dumping it. This results in minimized memory transfer and no idle cores.

The Technical Reality: During text generation, the model is memory-bound, not compute-bound. The time it takes to move the KV Cache from HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) to the chip’s SRAM is the bottleneck. MQA reduces the data volume of that move by a factor of $H$.

The Capacity Gap: MQA is a trade-off between nuanced response and memory capacity. The model loses the ability to store different types of information, as a single $V$ matrix must now store all nuances of information flow in the language.

The Surgery Trick (Uptraining): Google Research figured out a way to take an existing model with MHA and convert it to MQA by averaging the weight matrices of $H$ heads. This is called Uptraining. You then train this “Frankenstein” model for ~5% of the original training steps for adjustments. This yields an MQA model that is nearly as good as the original MHA but vastly faster.

🔥 Grouped Query Attention (GQA)

A “best of both worlds” solution used in modern models like Llama 2 and Llama 3.

How it works: GQA acts as an interpolation between MHA and MQA. Instead of having just 1 Key head (MQA) or $H$ Key heads (MHA), it divides the query heads into $G$ groups. Each group shares a single Key and Value head.

Equation modification: If you have 8 query heads, you might create 4 groups (2 queries per group). This reduces the KV cache by 2x instead of 8x, preserving more quality than MQA while still speeding up inference.

- MHA: 8 people (heads) are working on a project. Each person has their own unique filing cabinet (KV cache). It takes forever to move 8 cabinets around.

- MQA: 8 people share one single filing cabinet. It’s very fast to move, but they fight over the organization and lose detail.

- GQA: The 8 people split into 4 teams of 2. Each team shares a cabinet. It’s a balance between speed and organizational detail.

🔥 Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA)

This is the most advanced mechanism for attention, used in models like DeepSeek-V3. It is a sophisticated design for massive efficiency that takes a radical approach: mathematically compressing the memory into a low-rank “latent” vector.

KV Cache Explosion: As mentioned before, for a massive model like DeepSeek-V3 (671B parameters), storing the full Keys and Values for every token in a long conversation requires terabytes of high-speed memory (HBM), and chips spend more time waiting than churning.

MHA (Standard) stores everything. MQA deletes redundancy but hurts quality. MLA keeps the quality of MHA but compresses the data 4x-6x smaller than even GQA.

The Zip File Approach: Low-Rank Joint Compression

Let’s compare the math of MHA and MLA. In MHA, for every single token, we generate a unique Key ($k$) and Value ($v$) matrix for each attention head.

The Memory Problem: The $k$ is stored in the KV Cache. For 128 heads, for example, it calculates a massive vector of $128 \times 128 = 16,384$ floats per token.

For MHA, the attention score looks like: $$\text{Score} = q^T \cdot k$$

But for MLA, instead of storing the full $k$, it projects the input down into a tiny latent vector $c_{KV}$, which is much smaller (e.g., 512 floats). $$c_{KV} = W_{DKV} \cdot x$$

Now here is the catch: Naive compression and decompression would mean constructing a small latent matrix for every token and deconstructing it every single time the information is required, which defeats the purpose of compression.

$$k_{\text{reconstructed}} = W_{UK} \cdot c_{KV}$$ $$\text{Score} = q^T \cdot k_{\text{reconstructed}}$$

The Matrix Absorption Trick (Optimization)

Instead of reconstructing $k$ for every token, we can absorb the Up-Projection matrix ($W_{UK}$) into the Down-Projection matrix ($W_{DKV}$) and absorb the query $q$ into a new $Q$.

From the original equation: $$\text{Score} = q^T \cdot (\underbrace{W_{UK} \cdot c_{KV}}_{\text{This is } k})$$

We associate differently:

We change the order in which the matrix multiplication is performed.

How is this allowed? In linear algebra, matrix multiplication is associative:

$$(A \cdot B) \cdot C = A \cdot (B \cdot C)$$

We can move the parentheses! Instead of grouping $(W_{UK} \cdot c_{KV})$ to make the Key, we group $(q^T \cdot W_{UK})$ to make a new Query.

Note: The positional embedding information is left untouched. That rotational information from algorithms like RoPE is preserved outside the compression; it requires minimal space anyways.