Imagine you have to build a house. You cannot build a stable house using only massive boulders as walls (too big), nor can you build one using only tiny pebbles (too small). You need exactly the right-sized bricks.

The same analogy applies to linguistics. We need to find strategies to break down petabytes of language data into usable, atomic chunks. In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), these bricks are called tokens. Tokens enable us to transform a sizable amount of fluid language data into a discrete mathematical language that machines can process. It is the invisible filter at the heart of LLMs through which every prompt is passed and every response is born.

Let’s dive into the most popular tokenization strategies used in LLMs today.

1. Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

Early Natural Language Processing (NLP) models used to split text into words to form a corpus. During inference (i.e., when we want to generate text), any unknown word would be assigned an “out of vocabulary” token (<UNK>). Rare words like “uninstagrammable” were the usual victims of this process.

BPE is the most popular tokenization strategy used in LLMs, largely because it allows engineers to worry less about the problem of missing tokens. It received massive popularity after the release of GPT-2, GPT-3, and Llama. Most importantly, it is a simple, bottom-up, frequency-based strategy.

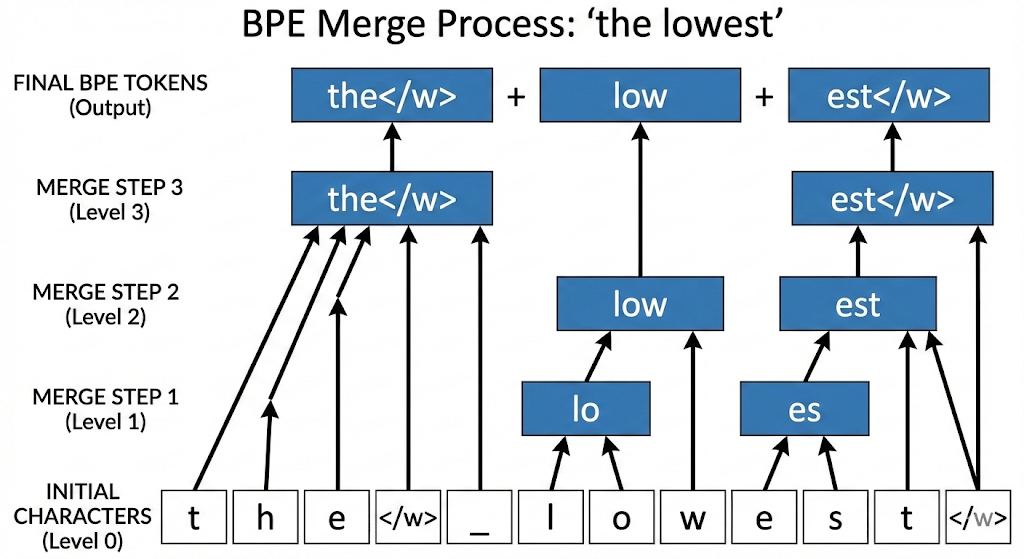

BPE starts with a vocabulary of single characters and then iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of characters until it reaches the desired vocabulary size. This creates a tree-like subword joining structure. By favoring frequent sequences, BPE ensures that the most common words and phrases are represented by a single token, while rarer words are represented by a combination of tokens. This makes BPE a powerful tool for representing natural language data in a compact and efficient way.

Modern Byte-level BPE goes even further by starting the process with the UTF-8 byte as a character. This ensures that the tokenization process is language-agnostic and can handle any language—even those that use non-Latin scripts or cannot be split by spaces, such as Japanese or Korean. While Unicode contains over 150,000 characters, using UTF bytes allows the vocabulary to start with only 256 tokens. The caveat is that the more fragmented the tokens, the higher the number of tokens required to represent a word, which increases the computational cost of tokenization.

The tokenization operates in 4 steps:

- Initialization: The process starts with a vocabulary of single characters.

- Pair Counting: The process counts the frequency of each pair of characters.

- Merge: The process merges the most frequent pairs of characters.

- Iteration: The process repeats thousands of times until the desired vocabulary size is reached (roughly 100000).

The “SolidGoldMagikarp” 🐟 phenomenon: This is a famous instance of “glitch tokens” in BPE. Since BPE is a frequency-based heuristic, One of the most bizarre side effects of BPE is the existence of “glitch tokens.” In GPT-2 and GPT-3, specific strings like “SolidGoldMagikarp” (a Reddit username) or “StreamerBot” cause the model to hallucinate or break down.

GPT 4 improved the BPE tokenization by adding Regex updates. For example, you generally don’t want to merge a word with the punctuation following it (e.g., “dog” and “.” becoming “dog.”).

2. WordPiece

WordPiece was developed by Google and gained widespread attention for its use in the BERT model and its derivatives. The WordPiece strategy addresses some of the limitations of BPE. Rather than relying solely on the raw frequency of subword tokens, it uses a maximum likelihood strategy to identify a meaningful vocabulary.

Superficially, WordPiece resembles BPE: it starts with a small vocabulary of single characters and iteratively merges them. However, WordPiece uses a statistical approach where scores are assigned to individual tokens in the training data. The score for a potential merge of two terms, $A$ and $B$, is: $$ \text{Score} = \frac{\text{Frequency}(AB)}{\text{Frequency}(A) \times \text{Frequency}(B)} $$ This formula ensures that common individual parts are penalized if they do not frequently appear together. This semantic cohesion guarantees that words appearing together are given more importance (a higher score) than parts that occur independently. The algorithm wrorks in two phases:

Training: The algorithm starts with base characters and then starts the merge process. For the part of the word that is in continuation it adds a special prefix ‘##’ so that the parts which start the word are distinct from those which trail in a word.

Inference: Unlike BPE, which memorizes merge rules, WordPiece operates by finding the longest possible subword match (a “greedy longest-match-first” strategy).

Given a word like “hugs”, it checks if the full word is in the vocabulary.

• If not, it looks for the longest prefix that is in the vocabulary (e.g., “hug”).

• It then attempts to tokenize the remainder (“s”) using the ## prefix (e.g., “##s”).

• If a subword cannot be found in the vocabulary, the entire word is replaced with the [UNK] (Unknown) token.

The model has certain pitfalls. The <UNK> token acts as a “hard cliff,” making it impossible to resolve very rare words. Recent research indicates that most tokens in WordPiece are start tokens (~70%), while only ~30% are continuation tokens. Furthermore, the model does not capture semantic links between words; for example, “advice” and “advises” are tokenized entirely differently.

3. Unigram: Chipping away unwanted tokens

Unigram follows the reverse strategy of learning tokens from data than BPE or WordPiece. It starts with a large vocabulary and then removes the least frequent tokens and it does this by selecting tokens based on the fundamental question: ‘Which breakdown of the text will maximizes the likelihood of the data?’

A single word can be tokenized in multiple ways. For example hugs can be tokenized as:

[hug, s][h, ug, s][h, u, g, s]

Each of these tokenizations will be assigned a probability score and the one with the maximum is selected as the likely winner. The mechanism uses Expectation - Maximization algorithm as follows:

1. Initialization: The model starts with the entire vocabulary and all the possible substrings in the corpus. Initial size is much bigger than the desired vocabulary.

2. Expectation (calculating Loss): The model calculates the loss for each tokenization by using the negative log-likelihood of the data given the tokenization. Essentially, it measures how well the current tokens can “explain” the training text.

3. Maximization (pruning): For every possible token in the vocabulary, the model calculates: ‘How much will the overall loss change if we remove this token?’. If the loss spikes on token removal (means that the token was important in compressing the vocabulary), it is kept. If the loss does not spike (token contributed very little to compression), it is removed.

4. Selection: The model discards bottom 10 to 20 % of the original vocabulary and the cycle repeats till desired vocabulary size is reached.

Because Unigram allows multiple segmentations for the same text, it relies on a dynamic programming method called the Viterbi algorithm during inference. When tokenizing a word, the algorithm builds a graph where nodes are characters and edges are possible subwords, then unrolls the path with the highest score. This ensures the tokenization is mathematically optimal rather than just a result of greedy merging.

Unigram is the default tokenization strategy used in SentencePiece. The model can use subword regularization during training to create a more robust tokenization. It means not picking the ‘best’ tokenization always but sometimes a ‘good enough’ tokenization. Also the model can use sampled segmentation which gives different optimal paths to tokenization of the same word, something chatbot applications really like. Unigram also gravitates toward tokens that compress the text most efficiently.

Recent comparative studies have shown that tokenization strategies affect languages differently. While BPE tends to perform better for Germanic languages (like English and German), Unigram (via SentencePiece) has been shown to be more effective for Romance languages (like Spanish) and Indic languages (like Hindi). This suggests that Unigram’s probabilistic approach may better capture the morphological nuances of certain language families.

4. SentencePiece: The Universal Adapter

Bold claim of sentences is that words are not separated by spaces, which is central logic to split token for many traditional tokenization strategies including BERT Tokenizers. The model treats whitespaces as part of the word. For example: ‘Hello World’ becomes _Hello _World.

Lossless Reconstruction: The model is lossless, meaning it can perfectly reconstruct the original text from the tokenized version. This is because it treats whitespaces as part of the word. The original text can be recreated by simply concatenating the words.

It is a common misconception that SentencePiece is a tokenization algorithm in the same vein as BPE. In reality, SentencePiece is a library and a strategy that can implement different segmentation algorithms, most notably BPE and Unigram. Unigram Integration: Models like ALBRET, T5, mBART, and XLNet utilize SentencePiece configured with the Unigram algorithm. This approach starts with a massive vocabulary and probabilistically trims it down, optimizing for the best segmentation of the raw input stream. • BPE Integration: Conversely, models like Llama 2 utilize SentencePiece configured with Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE). This allows them to benefit from BPE’s merge-based efficiency while retaining SentencePiece’s language-agnostic handling of Unicode.

Handling unknowns: The model provides an option called byte fallback, so whenever the model identifies a token as unknown, instead of adding it as <UNK>, the model can split the word into UTF-8 bytes and represent them as individual tokens. This is a more efficient way of handling unknown tokens and is used in models like Llama 2. It is a more efficient way of tokenization and is lossless.

SentencePiece standardized the NLP pipelines in ways that models consume text, by treating text as a continuous stream of characters and modelling whitespaces it can enable multilingual models like T5 and mBART.

5. Code Examples:

We’ll use sentencepiece for tokenization and compare results for different models.

import sentencepiece as spm

import os

# Configuration for training the SentencePiece model

# SentencePiece allows for subword tokenization, which helps handle out-of-vocabulary words.

options = {

# The source text file used for learning the vocabulary

'input': 'train_data.txt',

# The base name for the generated model (.model) and vocabulary (.vocab) files

'model_prefix': 'bpe_model',

# Number of unique tokens in the final vocabulary

'vocab_size': 4000,

# 'bpe' (Byte Pair Encoding) merges frequent pairs of characters/sequences

'model_type': 'bpe',

# Percentage of characters covered by the model; 0.9995 is standard for languages with large character sets

'character_coverage': 0.9995,

# When enabled, unknown characters are decomposed into UTF-8 bytes to avoid 'unk' tokens

'byte_fallback': True,

# Treats digits individually (0-9), preventing large numbers from being treated as single tokens

'split_digits': True,

# Prevents adding a whitespace prefix to the first token; useful for fine-grained control

'add_dummy_prefix': False

}

try:

print("Starting the training process...")

# SentencePieceTrainer.train takes the dictionary of options to build the BPE model

spm.SentencePieceTrainer.train(**options)

print("Training complete. 'bpe_model.model' and 'bpe_model.vocab' have been created.")

# Initialize the processor and load the newly trained model

sp = spm.SentencePieceProcessor()

sp.load('bpe_model.model')

print("-" * 30)

print("Model Metadata:")

# Retrieve the total number of tokens in the vocabulary

print(f"Total Vocab Size: {sp.get_piece_size()}")

# Special tokens are used for sequence boundaries and handling unknown characters

print(f"BOS (Beginning of Sentence) ID: {sp.bos_id()}")

print(f"EOS (End of Sentence) ID: {sp.eos_id()}")

print(f"UNK (Unknown) ID: {sp.unk_id()}")

print(f"PAD (Padding) ID: {sp.pad_id()}")

# Test the tokenizer on sample strings to see how it breaks down text

test_sentences = [

'Hello World! 1234567890',

'This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever'

]

for text in test_sentences:

print("\n--- Tokenization Test ---")

print(f"Original Text: {text}")

# encode_as_pieces: shows the actual subword units (tokens)

print(f"Subword Tokens: {sp.encode_as_pieces(text)}")

# encode_as_ids: shows the numerical mapping for each token

print(f"Numerical IDs: {sp.encode_as_ids(text)}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred during training or processing: {e}")

You can see the following output:

Starting training...

Starting the training process...

Training complete. 'bpe_model.model' and 'bpe_model.vocab' have been created.

------------------------------

Model Metadata:

Total Vocab Size: 4000

BOS (Beginning of Sentence) ID: 1

EOS (End of Sentence) ID: 2

UNK (Unknown) ID: 0

PAD (Padding) ID: -1

--- Tokenization Test ---

Original Text: Hello World! 1234567890

Subword Tokens: ['<0x48>', 'el', 'lo', '▁W', 'orld', '<0x21>', '▁', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '<0x36>', '7', '8', '<0x39>', '0']

Numerical IDs: [75, 380, 309, 476, 619, 36, 3924, 3964, 3959, 3993, 3978, 3983, 57, 3975, 3976, 60, 3974]

--- Tokenization Test ---

Original Text: This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever

Subword Tokens: ['This', '▁b', 'log', '▁is', '▁the', '▁mo', 'st', '▁un', 'inst', 'ag', 'ram', 'm', 'able', '▁b', 'log', '▁ever']

Numerical IDs: [1894, 304, 3284, 376, 321, 313, 312, 1008, 3313, 1325, 428, 3937, 341, 304, 3284, 1495]

The ! is fallen back to UTF bytes. and the word instagrammable is split into multiple subword tokens. Also, original text can be recreated right back by simply concatenating the tokens. And replacing underscore by whitespace.

Now we can try Unigram model. and see the same sentences tokenized differently.

from tokenizers import Tokenizer

from tokenizers.models import WordPiece

from tokenizers.trainers import WordPieceTrainer

from tokenizers.pre_tokenizers import Whitespace

try:

# 1. Initialize the WordPiece Tokenizer

# We specify the [UNK] token for handling words not found in the vocabulary.

tokenizer = Tokenizer(WordPiece(unk_token="[UNK]"))

# 2. Configure Pre-tokenization

# Before the subword algorithm runs, we need to split the raw text into words.

# Whitespace splitting is the standard first step for most English NLP tasks.

tokenizer.pre_tokenizer = Whitespace()

# 3. Initialize the Trainer

# We define our target vocabulary size and the special tokens required for

# downstream tasks (like BERT's [CLS] for classification or [SEP] for separators).

trainer = WordPieceTrainer(

vocab_size=4000,

special_tokens=["[UNK]", "[CLS]", "[SEP]", "[PAD]", "[MASK]"]

)

# 4. Train the Model

# The tokenizer scans the training file to build a vocabulary of the most

# frequent subword units.

tokenizer.train(files=["train_data.txt"], trainer=trainer)

# 5. Persist the Model

# Save the configuration and vocabulary to a JSON file for future inference.

tokenizer.save("wordpiece.json")

print("Training complete. 'wordpiece.json' created.")

# 6. Metadata Inspection

print("-" * 30)

print("WordPiece Model Metadata:")

print(f"Total Vocab Size: {tokenizer.get_vocab_size()}")

# 7. Testing Subword Tokenization

# WordPiece shines at handling rare words by breaking them into meaningful chunks.

test_sentences = [

'Hello World! 1234567890',

'This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever'

]

for text in test_sentences:

print("\n--- Tokenization Test (WordPiece) ---")

print(f"Original Text: {text}")

# Encode converts raw text into a Tokenizer object containing tokens and IDs

output = tokenizer.encode(text)

# 'tokens' shows the subword breakdown (e.g., 'un', '##insta', etc.)

print(f"Subword Tokens: {output.tokens}")

# 'ids' are the numerical indices mapped to the vocabulary

print(f"Numerical IDs: {output.ids}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred with WordPiece model: {e}")

You can see the following output:

WordPiece Model Metadata:

Total Vocab Size: 2609

--- Tokenization Test (WordPiece) ---

Original Text: Hello World! 1234567890

Subword Tokens: ['H', '##el', '##lo', 'W', '##or', '##ld', '[UNK]', '[UNK]']

Numerical IDs: [37, 180, 214, 52, 162, 418, 0, 0]

--- Tokenization Test (WordPiece) ---

Original Text: This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever

Subword Tokens: ['This', 'b', '##lo', '##g', 'is', 'the', 'm', '##os', '##t', 'un', '##ins', '##ta', '##g', '##ra', '##m', '##ma', '##ble', 'b', '##lo', '##g', 'ever']

Numerical IDs: [691, 58, 214, 102, 248, 194, 69, 660, 96, 875, 350, 209, 102, 155, 108, 173, 510, 58, 214, 102, 1240]

We can see the special character ## in the output. We can also see the breakdowns not having any semantic meaning. They are likelihood based.

We can try the Unigram model now.

# 'Unigram' is the default and usually recommended over BPE in SentencePiece.

options_unigram = {

'input': 'train_data.txt', # Path to the raw text file for training

'model_prefix': 'unigram_model', # Prefix for the output .model and .vocab files

'vocab_size': 1200, # Desired size of the final vocabulary

'model_type': 'unigram', # Specifies the Unigram language model algorithm

'character_coverage': 0.9995, # Percentage of characters covered by the model (0.9995 is standard for Latin scripts)

'byte_fallback': True, # Enables mapping unknown characters to UTF-8 bytes to avoid <unk> tokens

'split_digits': True, # Treats each digit as an individual token (useful for numerical data)

'add_dummy_prefix': False # Prevents adding a leading space (SentencePiece default is True)

}

try:

# 1. Train the SentencePiece model using the defined options

print("Starting Unigram training...")

spm.SentencePieceTrainer.train(**options_unigram)

print("Training complete. 'unigram_model.model' created.")

# 2. Load the trained model into a processor instance for inference

sp_unigram = spm.SentencePieceProcessor()

sp_unigram.load('unigram_model.model')

print("-" * 30)

print("Unigram Model Metadata:")

print(f"Total Vocab Size: {sp_unigram.get_piece_size()}")

# 3. Define test cases to evaluate how the model handles common and rare words

test_sentences = [

'Hello World! 1234567890',

'This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever'

]

# 4. Iterate through test sentences to visualize subword segmentation

for text in test_sentences:

print("\n--- Tokenization Test (Unigram) ---")

print(f"Original Text: {text}")

# encode_as_pieces: Converts text into subword strings (visual representation)

print(f"Subword Tokens: {sp_unigram.encode_as_pieces(text)}")

# encode_as_ids: Converts text into numerical indices for model input

print(f"Numerical IDs: {sp_unigram.encode_as_ids(text)}")

except Exception as e:

# Handle potential errors during training or loading (e.g., missing input file)

print(f"An error occurred with Unigram model: {e}")

The output is as follows:

Unigram Model Metadata:

Total Vocab Size: 1200

--- Tokenization Test (Unigram) ---

Original Text: Hello World! 1234567890

Subword Tokens: ['<0x48>', 'e', 'll', 'o', '▁', 'W', 'or', 'ld', '<0x21>', '▁', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '<0x36>', '7', '8', '<0x39>', '0']

Numerical IDs: [75, 268, 363, 340, 259, 473, 380, 1020, 36, 259, 283, 277, 536, 323, 348, 57, 316, 319, 60, 311]

--- Tokenization Test (Unigram) ---

Original Text: This blog is the most uninstagrammable blog ever

Subword Tokens: ['T', 'his', '▁b', 'l', 'o', 'g', '▁is', '▁the', '▁m', 'o', 'st', '▁un', 'in', 'sta', 'g', 'ra', 'm', 'm', 'able', '▁b', 'l', 'o', 'g', '▁', 'e', 'ver']